Making the Invisible Visible: A Review of ‘Mapping the Gay Guides’

(Note: Mapping the Gay Guides is completely non-functional on mobile — the menu does not work and visitors are unable to navigate off of the homepage. This was a major disappointment and definitely limits its ability to reach a broader audience. As a result, this review will focus entirely on the desktop version of the site which is significantly better in terms of functionality and design.)

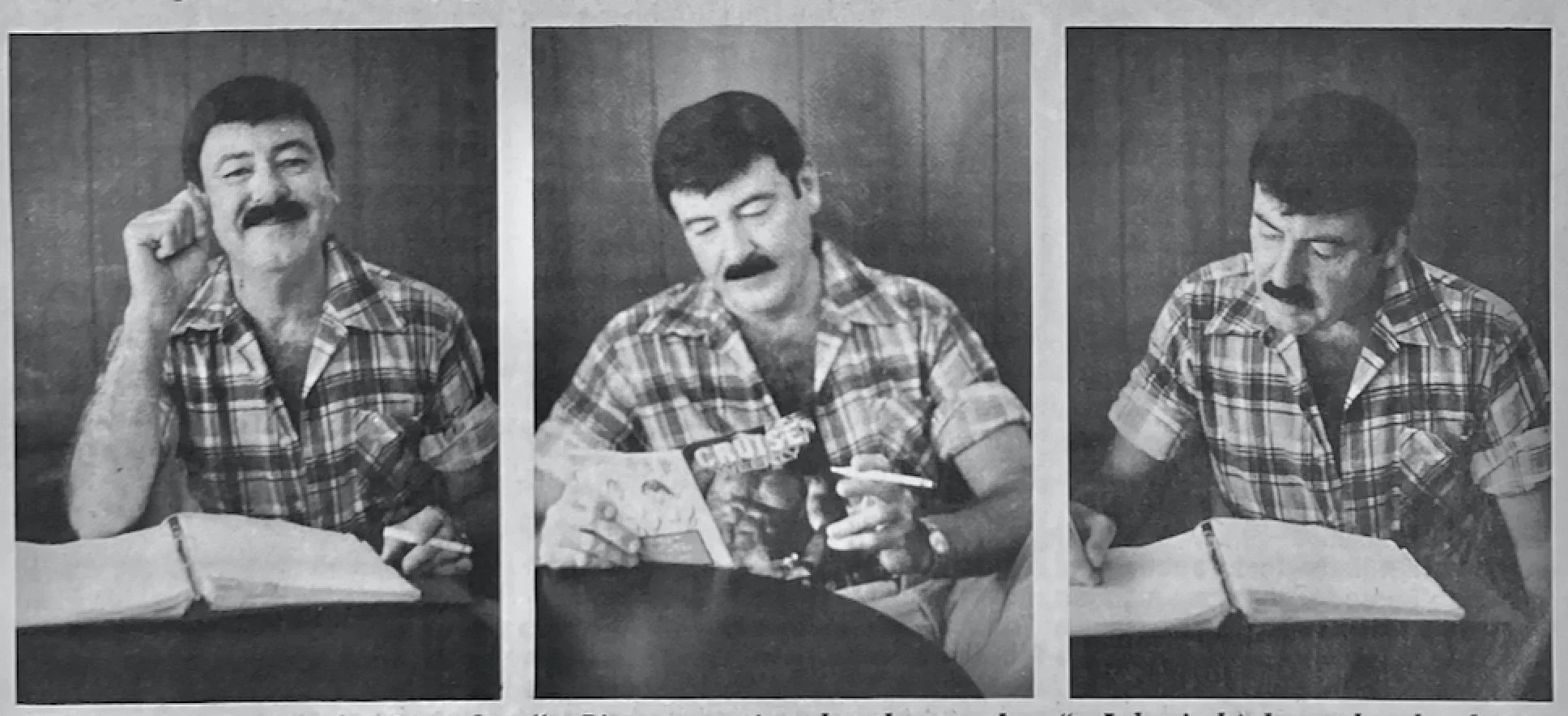

Throughout the second half of the 20th century, a Los Angeles man named Bob Damron published guide books for Gay men, highlighting gay-friendly bars and establishments across the United States. At a time where most states criminalized same-sex activity, these books were an essential resource that helped queer people stay safe while travelling. Damron printed 3,000 copies of his first guide in 1967 and updated the listings yearly until his company was sold in 1987. Bob Damron died of AIDS in July of 1989. His legacy, however, lives on to this day, and the most recent Bob Damron’s Address Book was published in 2019.

Damron’s books have immense value in the 21st century. Many of the bars, bath houses, and cruising locations within the guides no longer exist and because these establishments were illicit, official records were not kept. Additionally, because of the AIDS crisis, a large swath of the people who would remember this era of Queer history have been eternally silenced and are inaccessible for interviews. All of these conditions cause Queer history to appear invisible — something which is weaponized by those seeking to portray Queerness as a new-age fad indicative of moral decline. Damron’s books contradict this notion and, thanks to researchers Eric Gonzaba and Amanda Regan’s website Mapping the Gay Guides, their contents are now more accessible than ever.

Launched in February 2020, Mapping the Gay Guides (MGG) creates a comprehensive database of locations included in Damron’s address books from 1965 to 1980. This, the MGG team hopes, will help researchers to visualize the growth of queer spaces in the second half of the 20th century. Prior to Mapping the Gay Guides, Damron’s guidebooks were incredibly hard to access. Only one library had a full set of them and digitized copies were only accessible to those with an academic subscription. Thus, the project highlights one of the biggest strengths of the digital humanities in its ability to democratize information and make previously exclusive content accessible to a wide audience.

The site, which was created using HUGO, is easy to navigate on desktop and has a high-contrast design, making it accessible to the Visually Impaired. Additionally, this sleek and simple layout provides the site with a modern aesthetic that won't feel dated anytime soon. It is, however, incredibly text heavy and the only media featured are a few scattered images. This, paired with the lack of interactive elements or “widgets”, can make the site feel unengaging at times and could make it intimidating to more casual visitors.

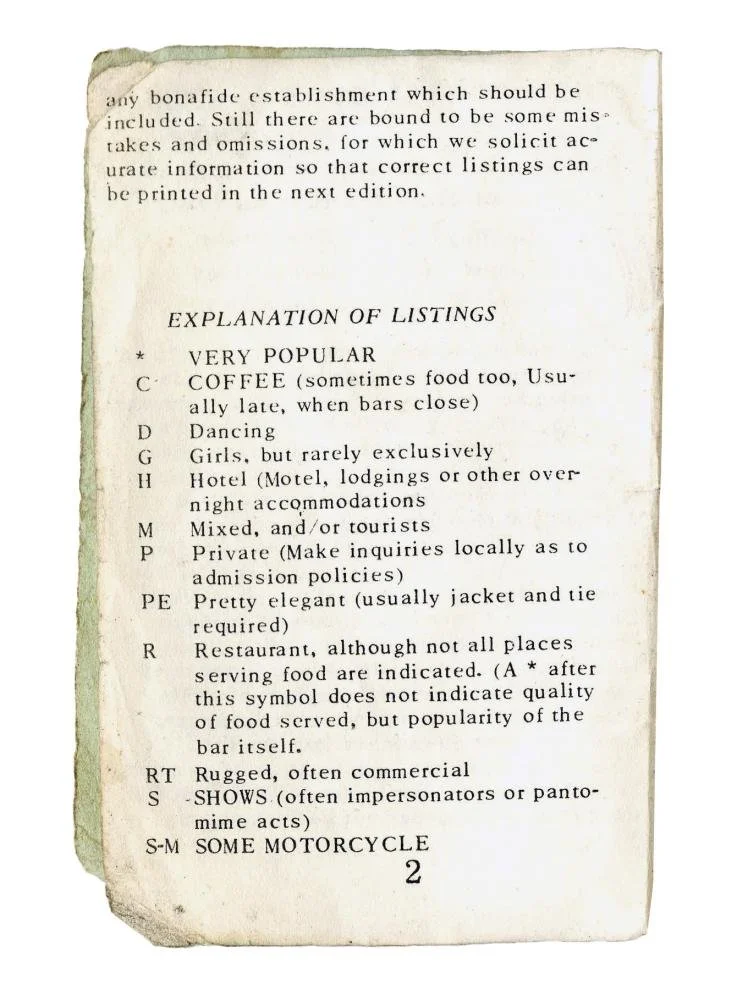

The map interface itself works as it should and is easily filtered via a number of criteria, including the date a location was added to the guide, the establishment's name, its type (bar, bath house, etc.), and its address. Additionally, researchers noted if Damron had specified any “amenities” — things a person should expect if they serviced the establishment. These “amenities” were noted in shorthand and included “BA” for “Bare-Ass,” “M” for “Mixed - some straights,” and “AYOR” for “At Your Own Risk.” In the past, these designations helped readers mitigate risk and differentiate between types of locations. Today, they provide researchers with essential information about the nature of 20th century Gay nightlife and act as filters for those looking into specific genres of establishments.

The map is, however, difficult to navigate at times for a number of reasons. First, it is confined to a narrow window which cannot be expanded, limiting the amount of information that can be viewed at once. This is compounded by the fact that map entries are grouped together regionally and do not appear as individual pins until users zoom in to street level. Both of these factors make it difficult to formulate “big picture” observations about the concentration of queer spaces within a given region. One is unable to see whether Damron had a bias towards any region of the country and it is difficult to pinpoint where a city’s “Gayborhood” might be. Perhaps then, Mapping the Gay Guides would benefit from a simpler, pin-based interface, like that of Queering the Map, an ongoing project where users plot their own queer experiences onto a world map.

Because of Damron’s own identity as a white gay man, his address books were often skewed toward those of his own community. Spaces for BIPOC individuals and women are a rare find in his guidebooks and are designated with a “B” for “Blacks Frequent,” an “L” for “Ladies”, or as being “(Latin)”. Thankfully, Mapping the Gay Guides includes a section calledVignettes, featuring blog posts on Black, Lesbian, and other minoritized queer businesses. These blog posts are a shining gem on the site and provide a venue for future scholarship that can continue to grow long after the gay guides are completely mapped. Additionally they serve as an extra layer of interpretation — making clear to visitors that, while Bob Damron’s Address Books tell a small piece of Gay nightlife history, other, more marginalized, queer stories still remain untold.